Me and my shadow economy

Urban underground or shadow economies are complex and intriguing. Based on my experience (both growing up in Cleveland Ohio and serving as executive director of the Dudley Street Neighborhood Initiative (DSNI) in Roxbury, Massachusetts), Sudhir Alladi Venkatesh's depiction of these unreported economic actives -- at least as it is described in the Boston Globe article below -- somehow doesn't capture the humble elegance of these edgy and deceptively sophisticated systems of exchange.

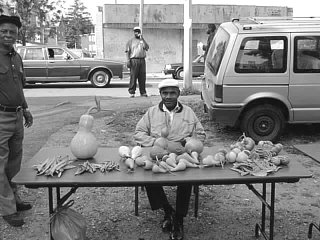

Urban underground or shadow economies are complex and intriguing. Based on my experience (both growing up in Cleveland Ohio and serving as executive director of the Dudley Street Neighborhood Initiative (DSNI) in Roxbury, Massachusetts), Sudhir Alladi Venkatesh's depiction of these unreported economic actives -- at least as it is described in the Boston Globe article below -- somehow doesn't capture the humble elegance of these edgy and deceptively sophisticated systems of exchange.There is a shady side (or two) to the underground economy for sure, but in many respects it represents a kind of "outlaw entrepreneurship" that aims to exploit the system but not the residents of the community. It can assume a variety of forms:

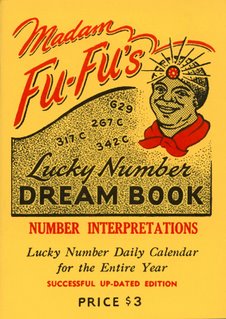

- In the '50s just about everyone in my neighborhood in Cleveland "played the numbers" (or "Policy") -- the people's version of what eventually became state-run Lotteries. Most people played for pocket change -- placing a bet on three numbers hoping they would match randomly drawn numbers (often after consulting "Dream Books" that could be purchased at the local drugstore. The books were loaded with 3-digit numbers matched to symbols. For luck, people would search the pages for symbols representing objects that appeared in recent dreams and play the corresponding number) . There was a local numbers runner (in our case, always someone who lived in the neighborhood) who came by your house and pick up your "policy slip" and wager. Of course, this was strictly illegal, but it never resulted in any Soprano-like violence within our community (Admittedly I never how the whole thing actually worked -- sort of like not wanting to know how sausage is made). For most who played, it really more of a social thing. "Hitting the numbers" usually resulted in payoffs in the range between $5 - $20, depending on the size of the wager (which averaged somewhere between a few pennies to a couple of dollars as far as I could tell).

- Taxi cabs in Roxbury (predominantly Black neighborhood in Boston) are about as scarce as liberals in the Bush Administration. One afternoon shortly after I began working at DSNI in the mid '90s I found myself running late for a meeting. After waiting impatiently at a bus stop for what seemed an eternity, I began walking/running down the street toward Dudley Square. A car passed slowly and pulled up to the curb just ahead of me. The driver rolled down his window, looked at me, grinned and said "The People's Cab at your service." He'd obviously been observing me for a while and sized up my situation. After a quick exchange, we negotiated a ride to my destination for $4.00. (GW)

A firsthand account of the vast "underground economy"and what an off-the-books mechanic can tell us about the health of our inner cities

ON A COLD FEBRUARY DAY on Chicago's South Side, two men are having an argument in a church parking lot. One is a local hustler who fixes cars and does his work wherever he can. This month, he is paying a local pastor to use the church parking lot. The week before, he paid a nearby store owner to work in a back alley.

On this day, he has just fixed the car of a local resident who is not happy. His customer thought the cost to repair his rusty 1986 Cutlass Ciera was $20, but the mechanic insists that his estimate was $30.

The dispute quickly gets out of hand. The mechanic refuses to return the keys to the car. The car's owner throws the mechanic to the ground, punches him repeatedly, takes the keys and drives away in his repaired vehicle. Bloodied and angry, the mechanic pursues him.

The mechanic makes his way to his customer's apartment building, where he begins yelling for him to come out. In full view of the neighbors, as well as the local block club president, he grows frustrated, breaks into the apartment, and walks out with a TV and VCR in hand. He utters a profanity, shouts "You better believe I get my money," and marches off.

One of the block club president's responsibilities is addressing safety issues on her block, and her constituents quickly remind her of this, beseeching her to call the police. But she instructs them to calm down. "Let me take care of it my own way," she pleads. "I'll call the police at the right time."

At the right time? I wonder. If a physical assault followed by a break-in and burglary is not the right time to call the police, when would be a more appropriate occasion? In my suburban southern California neighborhood, police would have arrived by this point.

In the inner city, however, a community's first recourse isn't always to turn to the authorities. For more than a century, many poor and working class residents of America's inner cities in particular those black Americans who were confined to urban ghettos by segregation and economic disenfranchisementhave been forced to hustle to make ends meet. And they've also developed their own mechanisms for resolving conflicts when a hustle goes bad.

These residents live in what the University of Chicago sociologists St. Clair Drake and Horace Cayton called the "shady world." Coined in the mid-20th century, their phrase describes the vibrant social life that arose around making money off the books. Then and now, not only residents, but churches, block clubs, stores, and other organizations have played a part in a shadow economy that most Americans neither see nor encounter.

Sudhir Alladi Venkatesh is professor of sociology and African-American studies at Columbia University. This article is adapted from "Off the Books: The Underground Economy of the Urban Poor" (Harvard), which has just been published. Click here to read the entire Boston Globe article.

Click here to read the entire Boston Globe article.

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home